In an age of democratic decline and persecution and discrimination, it is particularly important to draw attention to historic breakthroughs and the struggles that preceded them. This year it is one hundred years since women’s suffrage in Sweden was introduced – given that one was over 23 and did not belong to the category of beneficiaries, criminalized, untaxable, refugee, non-binary… or were hindered for practical reasons, a total of almost half the population if we include the men in these groups.

Yes, the image of the achievements of formal democracy has changed over time. Not very long ago, renowned historians stated that in 1909 the wealth lines were abolished by which universal and equal suffrage was introduced. The fact that the women’s category was still excluded was rather seen as a different topic and not as a public issue. Similarly with the restrictions for minority groups, which could at its best be considered a note in the margins.

Such telling of history does not pass without critique today. So how did the image of representative democratic developments change in the narratives of historians and the media? And what led to the category of women once winning the right to vote? Was it the ruling men who suddenly realized their unjust possession of power and gave the right to vote as a gift? Or was the democratic breakthrough rather preceded by many decades of hard-fought struggle against a stubborn resistance with much to be gained by preserving the status quo?

On November 10, Moderna Museet Malmö, Moderna Museet Stockholm, and Stockholm Women’s History arranged a full day of lectures by experts to celebrate the women’s category’s struggle for the right to vote and the opportunity to work employing their own artistic expression.

Why did the suffrage struggle take place at the turn of the 20th century?

Christina Florin began the day by pointing out the changing conditions of production: new occupations in the city, clerical work in the state bureaucracy, the postal service, the telegraph, all provided opportunities for women to become financially independent. Clerks were able to get maids, young girls who had moved to the city from the countryside, an arrangement that gave time to work for the franchise.

The leaders of the suffrage struggle could also have spouses of solidarity who backed up at home as the movement grew with advocacy, speaking tours, lists of names, lobbying. The average age of the fighters was high and far from everyone lived with men. Those who remained unmarried retained their authority and were not in need of solidarity from a spouse.

The most famous suffrage fighter in our time, Elin Wägner, got a job as an editorial secretary assistant, Ulrika Knutsson recounted. Employing a maid was made possible by the regular incoming salary of SEK 450 per month, which represented a quarter of what men received for the same work. Nevertheless, enough free time arose to write the suffrage movement’s literary classic, the novel Norrtullsligan. Raising the salary was not easy; the clerks were not allowed in the men’s unions but formed their own, while the wives of male clerks demonstrated against what they perceived as the unfair competition of female clerks!

The tactics of the Swedish suffrage struggle were tidy. The liberal and social democratic men in positions of power argued that the struggle of women should stick to the question of suffrage and that women should prove responsible and sober, all in order to meet the demands of ability. In Britain, the law-abiding suffrage struggle could testify that such promises proved to be empty talk. By the time the suffragette movement entered the stage in 1903, the organized law-abiding struggle against the oppression of the women’s category had been going on for two generations.

About a lesser-known element of the British movement, an internationally unique phenomenon in the suffrage movement, Carla Zaccagnini recounted. In 1913 and 1914, suffragettes entered museums to sabotage and create scandal in protest of politicians’ broken promises. A total of 29 works of art were attacked with sharp tools, scissors, daggers, hand axes; the most valuable work of art (£45,000) was Diego Velazquez’s oil painting depicting the naked Venus. The art sabotages violated profound expectations about women’s behaviour and pointed out with concrete precision that women like men possess destructive capacities.

According to Carla Zaccagnini, the sabotage actions showed what it took to win the women’s suffrage. A thesis – it must be inserted – about cause and effect that remains to be proven: the British right to vote for women was won only after the First World War in 1918 and then only for those over 30, living on the islands, with houses or households or a university degree. The women’s category was not included in universal suffrage until 1928 and in the British Empire the category won the right to vote only when the countries became independent from Great Britain, in India in 1947.

The emphasis on ability in the Swedish movement, protocol, voting procedure, and order, may seem a little too polite compared to parts of the British movement. But the setup contributed to knowledge and skill and to liberation through bold and self-confidence-boosting actions. Olivia Plender told about a previously unknown activity, The Fogelstad civic school’s courses for women from all walks of life: conquer the taburette, raise your voice in front of an audience – for many a great challenge but a prerequisite for participating in political life.

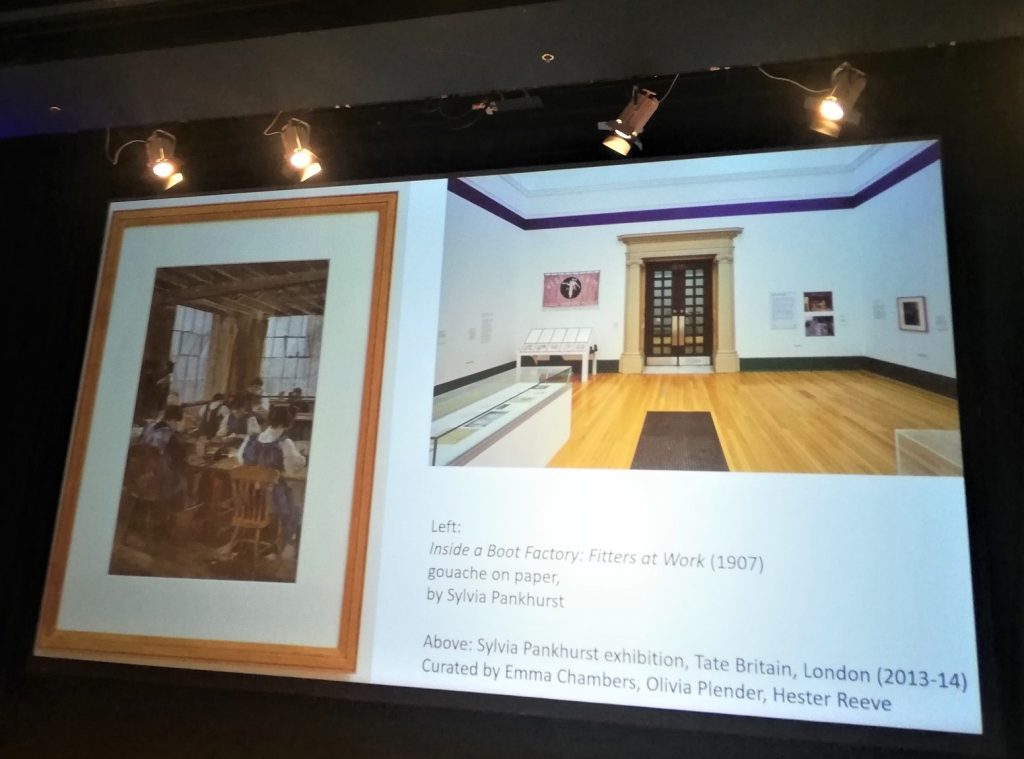

Olivia Plender and Carla Zaccagnini stressed that there has been a tendency to make the British suffrage struggle tidier and more respectable than it actually was. The democratic organisation of socialist, suffragette, and artist Sylvia Pankhurst in east London’s poor neighbourhood was an example of forgotten militancy. Here judo courses were organized in public parks, a female police army was organized as well, preschool and babysitting conducted, low-cost restaurants started, and jobs created for poor female fellows (a toy factory).

The lack of acquisitions of works by state museums and galleries has long created justified annoyance among artists. Olivia Plender spoke about an art action in 2013 in which a letter from Emily Davison Lodge led to Tate Britain exhibiting Sylvia Pankhurst’s 1907 painting Inside a boot factory, fitters at work depicting working women in a shoe factory.

The project also included an action with women and non-binary people who in today’s welfare system are treated punitively, like the suffragettes during the voting period. Defending oneself against everyday oppression means then as now to violate learned norms of accepted behaviour, raising one’s voice and using effective technology defending one’s own body against abuse.

Who was the first black woman in Sweden? A few years ago, the research project ”Atlas of Prehistoric People in Sweden” from Uppsala showed that the first Swedes were dark-skinned and externally varied. Rafaela Stålbalke Klos highlighted a later section in this story, an important and poignant chapter in Swedish minority history: Mazhar Makatemeles and her daughter Emmeline, nick-named Millan, and their life in the city of Kalmar.

In 1862, Mazhar Makatemele arrived in the sea-side town by boat from Transvaal, South Africa, after being sold four times as a slave. Here she came to work as a maid in the household of the educator and women’s campaigner Cecilia Fryxell. Mazhar Makatemele was baptized in the Church and in 1885 created a book of spiritual poems with the title “Andliga sånger”. Her daughter Emmeline came to work as a music teacher, both mother and daughter became profiles in the women’s law educational project the girls’ school Rostad and lived a peaceful bourgeois life together with Rostad’s principal and creator Cecilia Fryxell.

Mazhar Makatemele is buried in the cemetery in central Kalmar. In today’s South Africa, the choice of words on the headstone is considered grossly racist. After a protest by South African artists in 2017, the church administration set up an information board and arranged a ceremony in memory of Mazhar Makatemele, Black Sara, honourable citizen active in the city of Kalmar during the late 19th century.

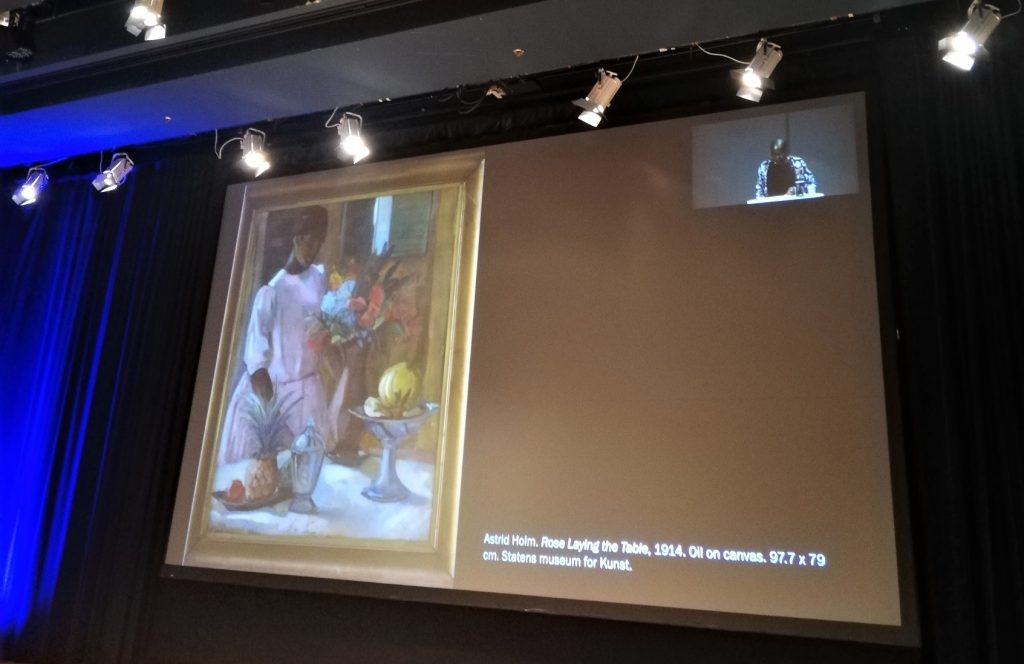

In her lecture, Temi Odumosu criticized the history of women’s rights as it is often told. Some stories and groups systematically fall into the background, as Sara Ahmed put it, ”trail behind”, are made into something marginal or end up in the shade. Combating such subordination can be done by researching particularities rather than generalities. Temi Odumoso took as a starting point Astrid Holm’s painting from 1914, Rose laying the table (Statens Museum for Kunst), which can be interpreted as Rose, when she as a maid sets the table, becomes an exotic object, a romanticized riddle rather than a subject and essential, equal person.

Temi Odumosu raised questions about what work is visible, and which is not visible, about the colonial systems, effects, and maintenance of the lives of historical Nordic women during the period. Works by Tora Vega Holmström were interpreted critically, the artist’s work in Algeria and Marseille presupposed and expressed a Nordic colonial approach. Tora Vega Holmström searched for the anti-colonial however in our time her work may be interpreted as an expression of the contrary.

The analytical methodology inspired further problematizing questions: How prevalent was it that maids were portrayed by women artists at the time? Was the portrait of Rose and her work, in its present day, with its pronounced and pervasive colonialism, an attempt at visibility?

Jessica Sjöholm Skrubbe spoke about the artists’ network, how women artists were not allowed into men’s associations – which were considered politically radical! – but must form their own ditto. Once there was the opportunity for larger exposés, for example at Liljevalch’s in the suffrage year 1921, their works were however measured according to the male norm and devalued by the critics.

Not long ago, it was said that the period after the turn of the century could not exhibit any women artists, as if these artists had not existed. But research and literature, such as Vanja Hermele’s Art – That’s How It Works (Doesn’t) from 2009, shows that the women’s category made up as much as a third.

The same period from 1900 to 1925 was discussed by Emma Severinsson in a lecture about how women’s magazines approached notions of The Modern Woman when the women’s struggle could be seen as a danger to the country: What if women’s liberation led to women not having the time to love a husband – that would truly pose a threat to the nation and nativity!

The period was indeed patriarchal-hetero: Before the voting year of 1921, women lost their authority if they married, while acting as an adult and working as an artist by definition and in practice meant a life without children and/or marriage. Even today, Jessica Sjöholm Skrubbe said, female artists have fewer children compared to their male colleagues.

The joint arrangement Moderna Museet and Stockholm’s Women’s History alternated perspectives and voices that spoke against each other in a thoughtful way. What began during the day as a supporting role – the existence of the maid – can be said to have crystallized into a central theme of future symposia: How had the struggle and conditions of women’s rights fighters and artists turned out without servants such as Rose, Mazhar, and the unnamed youth from the countryside? Would the suffrage struggle have arisen without maids?

Hopefully, today’s art education especially welcome the children of maids, servants, governesses, housewives from near and afar, whatever exterior and sexuality, so that artistically gifted people regardless of class may educate themselves and acquire their own artistic expression. And if not existing already, when, and how does this change happen?

Photos: From the Moderna Museum in Stockholm and from Liljevalchs, Djurgården, Stockholm

Previously published in Swedish in Fempers Nyheter 19 November 2021.

© Arimneste Anima Museum # 19