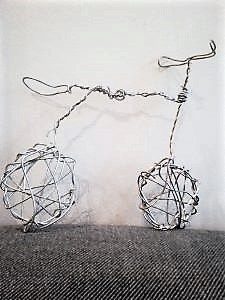

between literature, images of fruits and flowers, bicycles, and titan legs

The overall relationship between humans and the category of animals is much chronicled in European history. In fact, the human-induced killing of animals was acknowledged by Greek philosophers Aristotle, 384−322 BC, and Plutarch, 45−125 AC, respectively, as a kind of war. In the eyes of Plutarch, the killing of animals had profound impacts on human society; here quoted from Moralia, On the eating of Flesh, lecture II:

‘Even so, in the beginning, some wild and mischievous beast was killed and eaten, and then some little bird or fish was entrapped. And the love of slaughter, being first experimented and exercised in these, at last passed event to the labouring ox, and the sheep that clothes us, and to the poor cook that keeps the house; until by little and little, insatiableness being strengthened by use, men came to the slaughter of men, to bloodshed and wars.’

For most people, there were few or no other choices than to obey the master, the sovereign, the owner of the land, and take part in the killing of others, human and nonhuman, in wars and in hunting. Yet, most ordinary people subsisted on a mainly frugal diet, eating that which resulted from working the soil, collecting fruit and berries from trees and bushes, catching occasional fish from streams and lakes. In fact, the killing of other mammals, ‘meat’, was never a standard feeding ingredient for the European majority. The consumption of animal flesh by the society’s elite constituted rather a manifestation of power, towards other creatures, and towards the people.

However, there were parallel stories and parallel life approaches, such as the one suggested by Plutarch. Would history have staged differently, had Plutarch’s warning of the consequences of killing animals resounded through Europe? Some people may have listened and absorbed his wisdom; and ideally, the European continent would then have developed in more peaceful ways.

Anyhow, in the enlightenment tradition, there are to be found traces of Plutarch’s cross-species non-violence, in the writings of Montaigne, Rousseau, and Voltaire, and among some of the revolutionaries, both English and French, during and after the French Revolution. For instance, in his Tableau de Paris from 1782 and 1783, Louis-Sébastien Mercier states about the frequent slaughtering of animals in the city:

‘But his [a young bull] groans of pain, quivering muscles and terrible convulsions, his final struggle as he is trying to avoid an inevitable death; all this attests to the fear of violence, pain, and suffering. Look at the terrible pounding of his naked heart, his eyes darkening and languishing. Oh, who can contemplate this, who can listen to the bitter sighs of this creature sacrificed for man!’ ‘These streams of blood affect the morals of humanity as much as they affect the body and lead to the corruption of both.’

Mercier’s colleague Olympe de Gouges, in her revolutionary thinking, contested both human slavery in the French colonies and the suppression of women, proclaiming all humans in the world, of whatever sex or colour, to be equally and naturally included in the animal realm, stating humans to be the ‘most beautiful’ of all animals.

In the years following the French revolution, lamenting its failure, writers such as the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley blamed public butcheries and copious drinking habits for the domestic bloodshed that caused the revolution to collapse. Had the people been less accustomed to the slaughtering of animals in the streets, Shelley argued in a manner reminiscent of Mercier and Plutarch, they would not have accepted the violence that affected fellow Parisians, and maybe the revolution could have survived and escaped Napoleon’s dictatorship and wars.

I have hitherto made references to an almost exclusively male non-violence literature tradition. This is, however, no wonder since for most of European history people ascribed to the category of women – half of the population – were generally excluded from formal learning, qualified education, payment, equal hereditary rights, and sexual rights, civil and political rights. Women did probably write on the subject of hunting and domination; however, this writing is still yet to be discovered.

Nonetheless, in fine art, in the same era as Rubens painted the goddess Diana in a romanticising scene of hunting, several women artists painted themselves or other people instead holding animals, caressing animals, tables of fruits, tables of flowers: Lavinia Fontana, Anna Maria Van Schurman, Judith Leyster, Louise Moillon, Raschel Ruysch.

These hyper-skilled artists may indeed have felt, and known by experience, that Ruben’s Diana was not a real person; that she is a figurehead, a pictorial euphemism, an allegory deployed to depict a reality, which, unless you stage as the mock Diana, has little beauty in it.

Chances are these artists rather identified themselves with the hunted animal, thrown to the ground, robbed of its, his or her possibilities and autonomy by humans who might have chosen to do otherwise. Alternative myths of bravery told in these times may also have come to mind: The story of Francis of Assisi making friends with birds and wolves, and the legend of an anonymous woman defending a deer who, having fled through the woods from a hunting party, finds refuge at her human feet.

Despite the fact that world forest areas are shrinking to give way to feedlots for the mass production of beef, causing oxygen levels to fall and reserves for carbon emissions to disappear, thereby threatening the intertwined survival of human and nonhuman, hunting has nowadays become a popular sport. Indeed, modern hunting in the Northern hemisphere, although in itself disruptive to ecological systems, is marketed as an attractive leisure, accessible for people of whatever gender, seemingly natural, but artificially complete, with big heated vans, state of the art technological weapons, and latest countryside fashion clothes.

As many of the things we appreciate and enjoy in modern life are human-made, artfully or not, ranging from bicycles to titan legs, computers, plant meat stuff, and contraceptives, it can hardly be the artificiality of hunting that makes it remarkable. That which makes luxurious hunting remarkable – in every millennium – is rather the killing of those that cannot defend themselves, the outlook and practice of the one who has everything but goes to war against the one who has nothing but his, her or its own life.

First published in Contributor no 12 2016

Photo Planet bicycle by Alexandra Eklöf Gålmark

© Arimneste Anima Museum #2