A since long missing witness account

As a documentary writer one has to make an existential decision: If that which one is documenting appears to be an assault; ought one allow it to continue? Or should one interfere? What, more precisely, may decide which?

For one and a half century, non-humans have been objectified in slaughterhouses without being guilty of anything other than having been born. In post-industrial society it is a conundrum: Why has the meat industry not yet been transformed to attune with what is today known about the needs and rights of animals? How can it be that slaughterhouses are still operating? How is it possible that this phenomenon, the original model of concentrations camps, is allowed today? Is the reason that the public is not demanding the truth to be disclosed; that the drama of slaughter all too seldom becomes the object for muck-racking articles, critique, and performative representation?

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle about the conditions in the slaughterhouses of Chicago was published in 1906 (in Swedish 1906, 1925, 1928, 1945, 1950, 1977, 1983); Ruth Harrison raised awareness about the industrial aspects in Animal Machines 1964; the artist Sue Coe defied the industry’s prohibition to take photos, by drawing, in Dead Meat 1995; the investigator Gail Eisnitz interviewed slaughterhouse workers in Slaughterhouse 1997; Timothy Patchirat researched by participation in Every Twelve Seconds 2011; the poet Ted Genoways conveyed the story behind American pork in The Chain 2014.

In Sweden, the journalist Gun Lauritzson wrote about the working conditions in Aftonbladet 1980; the organization Djurrättsalliansen has several times documented the production; the photographer Erik Lindegren exhibited Walls of Glass; Scenkonstgruppen played Grismanifestet at Theatre Brunnsgatan fyra; the veterinary student Felicia Hogrell called out in Expressen this autumn; Norun Haugen disclosed the Norwegian pork business 2019 (recently aired on Swedish television) by asking: If the animals are treated as humanely as is asserted, why am I not allowed to come and see them?

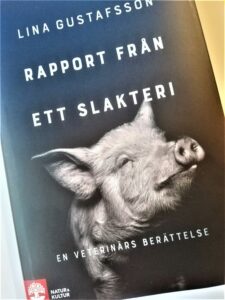

To this not enough noticed tradition the veterinarian Lina Gustafsson adds a witness report that until today has been missing. The veterinarian as testifier finds herself standing in the middle of skin parts, throats, hearts, cut up organs; concrete evidence for deeds, however not perceived as such. The matter is depicted hyper realistically without fauna metaphors – ‘under my boots some part from a trachea has got stuck’ – and forms a three months long moment of arthritis, inflammation in the breast, bronchitis, abscesses and cancer in limping, coughing beings showered to be taken down in the dysphonia and panic of carbon dioxide before they are cut with a knife to blead to death and transform into sausage, cutlet, pork loin.

The speed and the stress are on the maximal while at the same time all is standing still. Bodies are forced, beaten with tools, screaming, collapsing in acute stress reaction, trying persistently to escape, resisting. It is aridity and tragedy: big-raised bodies equipped with social capacity, mental ability, and olfaction – sharper than Canis lupus familiaris – in constant process of production.

The course towards participation is relentless. From the first pig leaving the crowded transport, scrutinized, and slaughtered without interference, to the first signature soon becoming many more, and then without a thought. The veterinarian resists and tries to keep her capacity for empathy and sympathy intact; to see and assist the individuals, but the pace and the high numbers thwarts her exertion. She counts the days as if she were scribbling them down on a prison cell wall: one, two, three until the last eighty fifth day.

Here, there is no achievable animal welfare, only degrees in hell. More or less sickness, many or not so many beatings. The only thing that can be done is to kill the animals “a little earlier”. Since the wrongdoing is fundamental, everything with the aim of solving or alleviating becomes absurd and the workers, without exception of male gender, may “thump” the all too familiar objects as an honest and logical act: nice ordinary people situated in a paid behavioral role, and the fellow being, the animal, is transformed, from creature to anonymous thing. So, the rational mind begins to demand responsibility: Who am I who is doing or contributing to this? Where do I stand in this production apparatus of death, this microcosm of doom?

After the second world war, strategists within the American military discovered an effective method to do away with the human resentment for hurting others; let the soldiers shoot digitally while listening to their favorite music in headphones. The method was employed in industrial assembly line production, assisting workers in coping and even performing well in jobs with the highest employee turnover. Headphones with music in the ears of the workers facilitated the late modern slaughtering business.

Thus, hell could be perceived as tolerable workday. With emphasis on perceived: In the study Killing for a Living from University of Colorado, USA, 2015 Anna Dorovskikh found that slaughterhouse workers risk being affected by a specific type of post traumatic participatory stress. The PTSD Journal explains: “These employees are hired to kill animals, such as pigs and cows, that are largely gentle creatures. Carrying out this action requires workers to disconnect from what they are doing and from the creature standing before them. This emotional dissonance can lead to consequences such as domestic violence, social withdrawal, anxiety, drug and alcohol abuse, and PTSD.”

The last chain in participation afflicts the consumer. In the 1870s the patriarchal upper class meat production was scaled up to become people food; leading to large areas of forests being felled to meet accelerated land and water demands (herding and fodder), emissions of nitrogen, ammonia, carbon dioxide, nitric oxide, methane (evaporation and excrement), animal-transferred epidemics and pandemics (zoonosis) such as COVID-19. Commercial killing in slaughterhouses became intimately connected with the planetary crisis.

Today, the consequences are acute: the risk of getting COVID-19 affects vulnerable groups (the elderly, the sick, refugees, prisoners, workers), imply lost jobs, large societal costs; countries, continents, and cities in quarantine. In February, China inaugurated a ban for consumption and trade with wild animals. To be able to evade new viruses, the international and Swedish animal agricultural politics must follow suit, give support to the alternatives (pea protein, mushroom protein, tempeh among others), and in this way hasten the much-needed structural transformation.

The author Maja Ekelöf’s Rapport från en skurhink [Report from a cleaning bucket] from 1970 was by Karl Vennberg written about as the hitherto most lucid and incontestable image of Swedish low pay workday during the 1960s. The same may be stated in reference to Lina Gustafsson’s image of Swedish workday in a slaughterhouse 2020. The truth is revealed, and the emperor stands naked.

However, for the book’s testimony to gain full significance, there is need for media commitment, and a veritable people uprising. According to the organization Human Rights Watch, slaughter work is a crime against human rights. And yes, not having to kill for commercial purposes ought to be a human right. And not having to be raised to be killed ought to be an animal right. A lot more is on the line than we used to think.

- Lina Gustafsson, Rapport från ett slakteri, en veterinärs berättelse, Stockholm: Natur & Kultur 2020

Translated from the Swedish. Originally published in FemPers 23rd of March 2020

© Arimneste Anima Museum # 14