in the novels of Norman Mailer, Carl-Henning Wijkmark and Arkadij Babtjenko

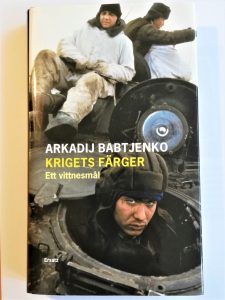

It ought not be allowed to happen in such a beautiful place, Arkadij Babtjenko exasperates in his testimony from Chechnya, One soldier’s war in Chechnya (2007). When the sun is shining most wonderfully above the apricot trees, the bodies of dead comrades return from the front in tinfoil bags.

The contrast, between the beautiful surroundings and the grimmest harvest of human actions, tears apart the emotional defence. Here, where everything could have been beaming and beautiful, everything is beaming and ugly. Why these actions? Granted the abundance of the world, how can it be that a good life for everyone is wasted in ravaging and killing? What is found at the base?

Those who order and execute the killing are almost without exception men. Thus, a person included in the category may specifically be called upon to respond to the question. A writer belonging to the category may be offered special opportunity to give an answer.

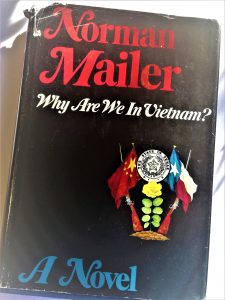

The recently deceased author Norman Mailer left behind a reputation as a male chauvinist and criticizer of women’s liberation. Nevertheless, Mailer may be read as a satiric agitator of stereotyped masculinity, a writer revealing the cult of conventional male culture.

The novel Why are We in Vietnam? from 1967, in Swedish 1969, was perceived as an allegory of the US war against Vietnam. However, not only does the story offer an image of the war on the other side of the globe, it also comments upon an historical and current reality, and it gives an answer to questions about the origin of violence.

Image and alphabetic character; metaphor and reality. The hunting of animals prepares the ground for and gives the 18-year old protagonist DJ practice in accepting the role as soldier bargaining chip in US world politics.

Directed by older men, including his father, DJ takes on the traditional Western masculinity that focuses upon the domination of others. In mantra-like despair, DJ rants about his father’s actions, those that can be explained by ’that dried-out sunbaked smoked jerkin of meat his cowboy fore-ass bears used to eat.’ The team of hunters start ’a war’ between themselves and the animals in which ’the hunthills rang with ball’s ass shooting.’

The expedition is led by the chief executive of the company, Big Luke, in charge of the ’superhuge kettle of lobster shit in volume dollars’, ordering the helicopter to circle over the skulls of the chanceless animals. The consequences of violence and death make up the ’flavour of the secret jellies and jams used in the black mass of real military lore.’

The only way to evade the imposed death scare is to join in the killing. To kill becomes the outlet for a sexuality in which the male, to be accepted as normal, must continuously coerce. The practice is accomplished, the enjoyment directed, what remains is the upgrading; from animal to human. In the words of DJ: ’The gnat in the navel of the whole week of hunting’ and: ’Think of cunt and ass – so it’s all clear’.

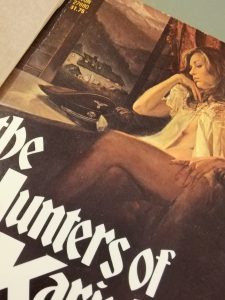

Carl-Henning Wijkmark’s debut novel from 1972, The Hunters of Karinhall, now in a new edition from Modernista publishing, answers the questions about violence in a way that resembles Mailer; Nazism as a lifestyle of Göring, second highest man in the Third Reich. Already in 1934 Göring set up concentration camps, and later on he was responsible for the rearmament and the redoubling of the conscription time.

Göring endeavoured to be an animal lover, but loved to hunt, slaughter and perform the cutting up. And to organize yearly hunting parties where Europe’s top politicians assembled.

The hunting site of Karinhall stands as a model for a nature in which the human impulse to kill is ’stimulating’. The long period of peace has become tiring for the nerves, and the deer in the woods lift their ’white rumps obscenely and contemptuously in the air.’ The men need ’something living to shoot at – that is the whole attraction of the thing.’ In the same way Göring has eliminated everything ’week or sick or eccentric’ from the German forests, so he and Hitler have ’purified society from foreign and degenerative elements.’

Metaphors and thesis blend in Wijkmark’s deftly told pornography; Göring offers the elite men meat, and meat again, sheep slaughtered by his own hands, and, above all, human living flesh, prostitutes transported from a concentration camp for women, bribed with promises of dismissal, and, perhaps, marriage. The metaphors of war are legion, limbs rise and let off like ’cannons’, the men are in ’the saddle’; and the women, perceived as selected ’female flesh’, are ’rammed’, ’attacked’, and ’served’ in a milieu of the finest castle interiors; animal skin tapestry, animal skin sofas, and animal skin leather hosen.

The women play the role of anxious willing ’prey’ and ’chattels’, marked with numbers, Orwellian ’hunting hostesses’ in the ’House of joy and exuberance’. Perhaps it is due to a flight of fancy sex liberalism of the 1960s, making the women seem so compliant, perhaps it is the trick of Wijkmark; the perspective, the illusion is steadfastly owned by the male protagonists. The nature-attuned Göring copulates with jaunty German women in long paragraphs, and soon the reader, regardless of gender, is cornered as well.

The dehumanization of others, in different degrees in relation to different categories, reaches its stylish climax at the end of the novel. Il Duce degusts the result of today’s kill, places the thin snipe halves on his tongue – and is plunged into ecstasy. The foundation for the Rome – Berlin axle is secured.

Politics and satisfaction of the authoritative male body are merged into one. But not as Wijkmark has been interpreted hitherto, in excess and gluttony of food and sex, but rather as an option of a certain type of food and a certain type of sex. Culturally formed choices presented as inevitable expressions of Western masculinity.

A more concrete and explicit scapegoating of nature, and misogyny, where women are solely body and animal, and animal is the same as meat and object, than The Hunters of Karinhall is difficult to find. The example in Wijkmark’s novel, Göring, is well chosen; the Nazi contempt of women was indeed extraordinarily profound, and politically performed; the whole of the German people perceived as a bitch to be seduced and screwed by the means of simple emotional arguments.

Alongside civilians, women, children, and the old, it is young men of primarily under class that for centuries have constituted the cannon fodder for the conquest wars. ’Do you get that into your heads, you fat, smug generals who sent us off to slaughter’, cries Arkadij Babtjenko. The boys, pulling their male limbs in fear and hatred and madness, are transformed into objects and dead meat ’just like pieces of barbeque meat, before we get sent off to the meat grinder, then it is easier for us to die.’

The absurd war and alienation. The greedy war against the people taking a leap forward by the violence against animals; in metaphor, and in concrete action. Conditioned by a sexualized male cult. Affecting also men. No, it ought not be allowed; yet this is what is staged, although the experience, if not the insight, was already so distinctly formulated.

Previously published in Swedish in Aftonbladet Culture 12 August 2008

- Babchenko, Arkady, One soldier’s war in Chechnya; translated from the Russian by Nick Allen, London: Portobello, 2007

- Babchenko, Arkadij, Krigets färger, ett vittnesmål, translated from the Russian by Ola Wallin, Stockholm: Ersatz, 2007. Uppdatering, ny upplaga: Krigets färger; Dagar i Alchan-Jurt, övers. Ola Wallin, Stockholm: Ersatz, 2022

- Mailer, Norman, Why are we in Vietnam? A Novel, New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1967

- Mailer, Norman, Varför vi är i Vietnam, translated from the English by Erik Sandin, Stockholm: Bonniers, 1969

- Wijkmark, Carl-Henning, The Hunters of Karinhall, translated from Swedish by George Bisset, New York: Avon, 1976

- Wijkmark, Carl-Henning, Jägarna på Karinhall, Stockholm: Modernista, 2007

- Photo: the exhibited books are from the Arimneste Library; the Nobel Library; the National Library of Sweden

© Arimneste Anima Museum #9